Rip This Joint

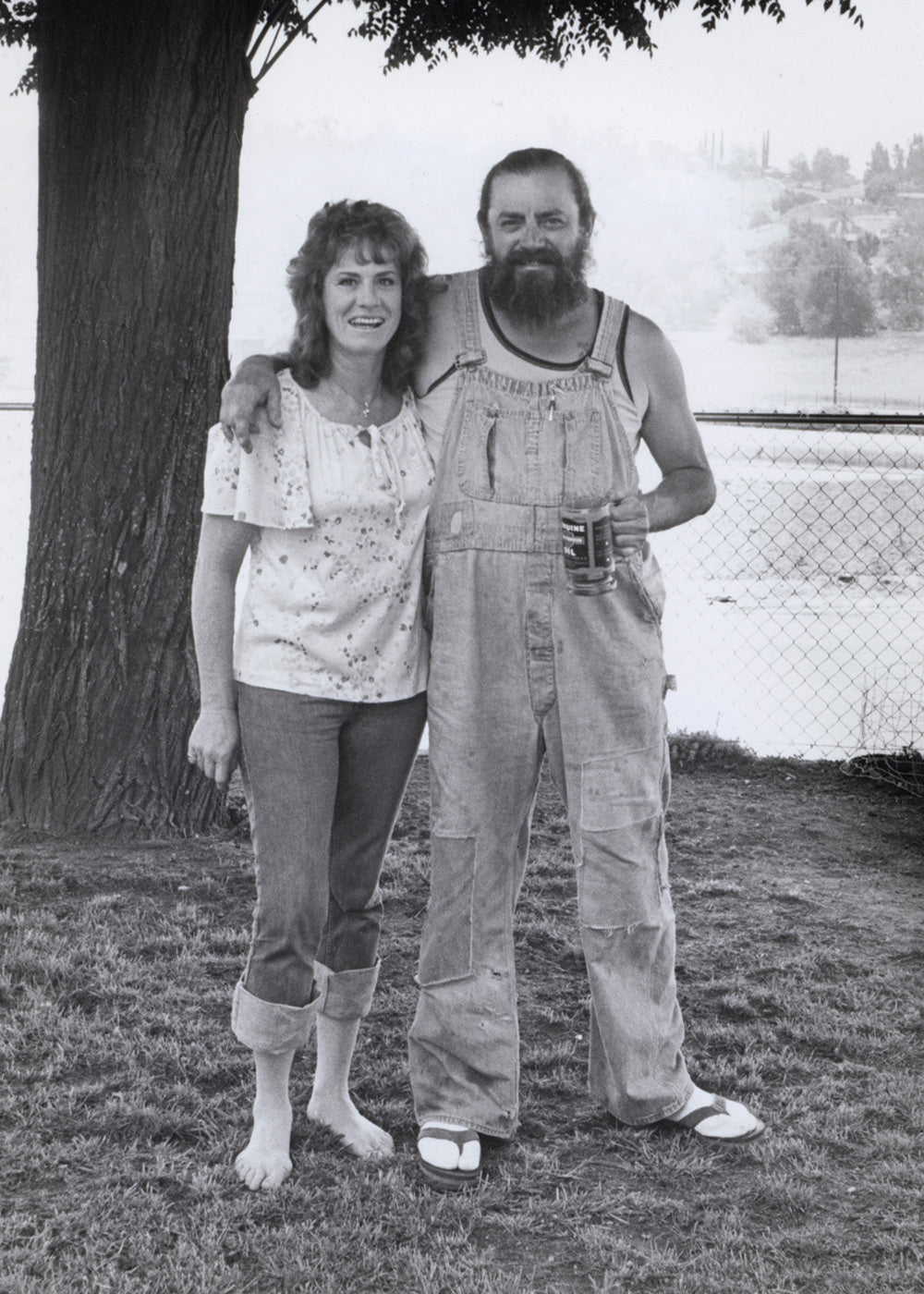

Legendary leather ass Rip-A-Roo from Berdoo remembered by his daughter.

Rip was too busy living life to consider the influence he’d have on future generations of bikers. The Manson Family were on the news, trucks had camper shells and macaroni and cheese was for dinner. We had a pink house in the suburbs and my dad owned a refinishing company on the North side of Long Beach.

Probably an attempt at giving him a son, I was born the sixth and last daughter of Rip and Patty Rose. The truth is, I didn’t know my dad very well, at least not the hard-wrenching dirtynecker Rip’s Run readers knew. From my vantage point, he was a compelling, formidable, obsessive and intelligent man who was more than capable of charming or strong-arming to get his way. Even before he was known as the man that travelled from bike shows to racetracks, to motorcycle rallies across the States, when he showed up, you knew it. Striking and imposing, he always commanded a room. To me, he was both intimidating and admirable.

You may be surprised to know that there were seven of us at home relying on him. One time I was talking to a clerk at the Easyriders Store in Hollywood in the early 1990’s, and the guy was arguing with me. He said that Rip didn’t have a family. I remember thinking that that would be a weird thing to lie about, but I understood. My dad kept his family life separate from his to keep us safe and to make things simpler for himself. Mom knew he had a way with the ladies, but she was content as long as he came home to her. Dad didn’t bring many people around us, but he had a small group of friends that he trusted. The loud and rowdy troop was very kind to me. I marveled at their colorful monikers; names like Spider, Popper, Easy Ed, Heavy and Tiny. My sisters tell stories of waking up with hairy, stinking bikers passed out on the floors of their bedrooms. I guess they figured that it was as good as any place to sleep it off.

When he wasn’t building bikes or refurbishing furniture that fell off somebody’s truck, he was raising hell with his cronies and contributing to Paisano Publications behind the scenes. At the magazine, he wrote tech tips, worked as security and helped with photo shoots. As the baby of the family, I spent most of my time with my mom or older sisters. Always busy, my mom was skilled at making things; sewing clothes, knitting blankets, cooking, leather working, canning fruit, curing meat, or embroidering. It never stopped. I swear, she never got enough credit. That woman took a lot of shit and her work was never, ever done.

In the middle of my first grade year we relocated from Orange County to the Inland Empire a.k.a. Berdoo. Instead of going to the beach with my sisters after school, we were helping feed chickens and tending the garden. The siblings that were still in the home quickly acclimated by making friends and doing what teenagers do. One of the garages was doubled in size so my dad would have plenty of room to store and work on his bikes. The front garage was converted into a paint station for parts.

Rip still made regular trips to Sturgis and Daytona Bike Weeks and frequented local uphill, flat track and drag races. With a mentor like Lou Kimzey, the founder of Paisano Publications and teachers such as Kim Peterson, Pete Chiodo, Keith Ball, Tex Campbell, and Lizette Hottinger teaching him how to operate a camera and write magazine articles, my dad was in good hands. He was the kind of guy that would stop at nothing to master something he wanted to know. I always admired that about him.

He combined the tips he’d learned from his bros at the magazine with his love of the open road and started Rip’s Run in the summer of 1986. The monthly column chronicled his travels to the big annual motorcycle rallies as well as lesser-known biker-friendly businesses throughout the US. Once Rip’s Run was a thing, he was home for a couple weeks at a time and gone for the same, logging upwards of 140,000 miles per bike.

In the early days he’d labor over his article for a couple of days then give it to my mom to type up on her typewriter before he turned it in at work. He’d get pissed if she corrected his spelling or grammar, so finally she just left it. His days were spent in the garage working on his bikes or on the road riding them.

Wherever he was, he was stoned. A greenhouse/lathe house was built so that my mom could grow grass for him. To this day, I’ve never known anyone to smoke as much weed as he did. He seemed happy at his “ranch”. When we heard him coming on Darling, tearing up the hill after exiting the freeway, my mom or me had to drop whatever we were doing and open the fence so he wouldn’t have to wait. At the time I didn’t know what an Evo Softail was, nor that he had the third one ever made. It was a ritual; I’d sit quietly as my mom helped him unload bags of laundry and his Nikon cameras packed snuggly in their Halliburton homes. I wondered where he’d been and what he’d done. In my late teens, I realized that it was as much my responsibility to facilitate a relationship with him, as it was his. I tried getting beyond my apprehension by connecting to what I perceived as his passion. Once I asked how his trip had gone. “It’s hard work,” he said, as if I’d assumed otherwise. I don’t remember the first time I looked through the magazine. Probably around the time I grew boobs of my own and started cussing and smoking in front of my mom. But I absorbed everything I could from the Popular Photography and American Photo magazines he’d bring home from the office.

Images by Mann Ray, Ellen Von Unwerth and Helmut Newton evoked my love for photography. On my 16th birthday, my dad finally thought I was responsible enough to care for my own 35mm camera. He took me to a camera shop in Berdoo and bought me a used Konica and gave me a roll of T-max 400. My friends and I climbed on roofs and found wet alleys to shoot in. I was so excited to get my proof sheet back from my dad’s photo lab. One look at it and he said, “Oh, you like that artsy-fartsy stuff.” I thought that I had failed.

The magazine was another symbol of how my dad seemed to separate his life. He had friends from one side of the country to the other. People respected him across the globe, yet they saw a side of my father I’d only get glimpses of. He and I didn’t spend much time together, but when we did, we did some cool shit. In 1988, he took me to Tijuana for the Solo Angels’ annual Christmas toy run. I learned what cold was when it started raining on our way back about a ½ hour North of San Diego. He’d take me on rides around town once in a while, probably after he’d replaced a part or after a tune up for a shakedown. I went with him to the office once. I wanted to intern there, but it never happened. Around that time, he was given tickets to the premiere showing of the film, Harley-Davidson and the Marlboro Man. A friend and I met him at the Groundlings Theatre in Hollywood. It wasn’t too fancy a shindig, but I felt pretty rad to be a part of my dad’s lifestyle, even if it was only for a couple hours.

In my early twenties I moved to San Diego. Billy Grillo was a good friend of my dad’s and whenever he came through with The Grateful Dead, he’d roll out the red carpet for him. They were scheduled to play the Sports Arena and my dad invited me. I got a taste of what it was like for him on the road when we blew past the people waiting in line and was directed to park by the tour bus. After watching a few songs from backstage, we took our seats. I’d never owned a Grateful Dead record, but thoroughly enjoyed the creative atmosphere. Joints were being passed and of course, he partook.

Soon after that I relocated to New York City to make art with my best friend. But it wasn’t long before my dad was diagnosed with throat cancer and I found out he had started chemotherapy. I remember that he took me to breakfast in Staten Island on his bike and we kept our chat light.

After deciding my time in New York was over, I wanted to live somewhere where I didn’t know anyone and could completely rely on myself. I attended my sister Debra Sue’s wedding in Las Vegas, then went on to Phoenix, Arizona.

In addition to battling cancer and traveling for work, his time and energy were consumed with bringing an idea to fruition. He’d been diagnosed with diabetes about 10 years prior and wanted to help raise funds to find a cure for diabetes. In March of 1998, I received a voicemail from my mom. I could tell something was very wrong and feared for my father’s health and safety. When I called her back, with tears she told me that my dad was okay, but that my sister Debra Sue had been killed in an auto collision. This sent shockwaves through our family and her community of friends.

Our dad coped with the loss of my sister by engaging even more deeply in his commitment to end Diabetes. He worked closely with The American Diabetes Association and enlisted the support of the Davidson Family, motorcycle industry leaders and bikers touched by diabetes. Three hundred riders converged on Glen Helen Pavilion from a few start sites in Southern California, in June, 1998, and Rip’s Bikers Against Diabetes Ride debuted. It was his dream to unite the biker nation and expand this ride countrywide.

In 1999 those that attended the second BAD Ride would see what his family, friends and co-workers had accepted; his body was succumbing to the ravages of cancer. His spirits were high, being surrounded by his family and the support of the biker community. In February of 2000, he passed away enveloped by the love of two of my sisters, his sister, and my mom.

We spread his ashes in one of his favorite riding locales near Big Bear in the Southern California Mountains. Spearheaded by family friend, motorcycle attorney Steve Schapiro, Rip’s B.A.D. Ride continued to bring tens of thousands of motorcycle enthusiasts together in several sites countrywide and ultimately raised over $4 million for the ADA by its final run in 2015.

A couple of months before his death, Rip was modest when notified that he would be inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame. He’d been too busy in the wind, building, customizing, photographing, writing, working and partying to consider his legacy: live a life you love. He used his skills and passion and didn’t let anyone get in his way. He took no shit and only did exactly what he wanted to do.

Sharing my story with Choppers Magazine readers has given me the gift of seeing my dad from a new perspective. After a lifetime of being vexed by his often-cantankerous insolence, by pouring through his work and talking to his friends twenty years after his death, I’m learning about how and why he inspired so many. It was never a matter of rebelling against the establishment or proving how cool he was by having the newest piece of whatever; it was all about being true to himself. He had to be free to live life on his own terms. He had to ride fast and far and often.

- Glitterfist

Story by Glitterfist

Photos provided by Kim Patterson and the Rose Family Archives

I lived at the apartments by the shop wandered over there and met Rip and Patty. I used to help Rip with deliveries and met a lot of people and the stories I could tell. Your Mother Patty was such a sweetheart God bless you all.

RIP was a friend and a nice guy. Nice Tribute. Peace and Love

While I never met Rip – I sure heard about him many times about what a legend he was. Incredible story – thank’s for helping us all know so much more about him, his life, and everything that he accomplished. Rip was the real deal. He lived and breathed motorcycles, and the lifestyle. Life sometimes helps us turn the right corners at just the right time. I’m the bass player, and back-up singer for the Full Throttle Band (a classic rock, blues and metal band). We were absolutely honored to be invited to play at one of the final B.A.D. Rides. And we were thankful to be able to help the cause. R.I.P. Rip. Ride Forever…

What a wonderful tribute to your dad! He definitely ALWAYS had a presence. He was a good friend and stellar story teller. God Bless You Kristina!

Leave a comment